SYNCHRONICITY ITSELF

Exploring Carl Jung's Concept of Synchronicity and Its Potential Role in Adult Development

— by Ralph Williams

Life is full of surprises, or so it is often said. These words are spoken now and then to remind us that all things change with time and around every bend there always lies the possibility that something new and out-of-the-blue could happen. Expect the unexpected! This phrase is used on occasion too as a clever reminder that unanticipated or unusual events are inevitable, and we should try our best to be braced and prepared for their sudden arrival. Sometimes though, things will occur in life that are so peculiar and ironic that they seem to extend beyond the limits of what we would normally expect, even from the unexpected. Imagine, for example, that you are writing an old friend after years of lost contact, and in the middle of your composition, the phone rings and it is the very friend you are writing. Or, suppose that while driving to work one day you start to sing a few bars from an old musical, and a few seconds later, the song comes on the radio. Most of us have encountered events like these from time to time—events that seem all-too-timely or suspiciously uncanny. It might involve the peculiar way that a helpful person or some much-needed information happens your way as if air-dropped from heaven straight into your lap. It might also occur through a series of events or a chance meeting that seems to redirect a project or career path in a highly fortuitous manner, as if the doors of opportunity were being opened by fate herself. These experiences are typically referred to as coincidences, but are they always pure coincidence?

Chapter 1

Nature of the Phenomenon

Coincidence is no stranger to life, of course, and given that we live in a dynamic world of endless interactions, it would be a bit bizarre if coincidental events never occurred at all. But sometimes, the irony of an experience can be so profound and the coincidence so precise that it becomes difficult to dismiss to mere chance. But if not coincidence, what then? This question has troubled humankind throughout the ages and has given rise to a host of explanations and mythological tales. Ancient cultures and polytheistic beliefs would usually interpret events like these as signs or omens from the gods—something to either be feared or revered depending on the nature of the coinicidence. Some would even plan an otherworldly instigator behind these events, known as a “trickster”. In Greek mythology, for instance, hermes is depicted as a mischievous, wing-footed god who moves between the godly and earthly realms, delivering messages and taking pleasure in staging mishaps and surpises for humans. Hermes is also portrayed as the guardian of human boundaries, including those between life and death, waking life and sleep, and the god-realm and humans. Roman mythology has a very similar character in the winged messenger-god, Mercury, who is typically depcted with little wheels under his feet to help him deliver lucky moments and auspicious news quickly. In Norse mythology, Loki is the shape-shifting trickster of the unseen world, and to the Ashanti people of West Africa, it is the god, Anansi. In Ancient Chinese mythology, the trickster character is embodied in the clever and disobedient monkey, Sun Wukong, while in the sacred ythology of India, it is Krishna. To the Polynesian Islanders, it is Maui, and in the stories of the American Plains Indians, it is typically the trickster Rabbit and Coyote who are placed behind disrupting events and lucky coincidences.

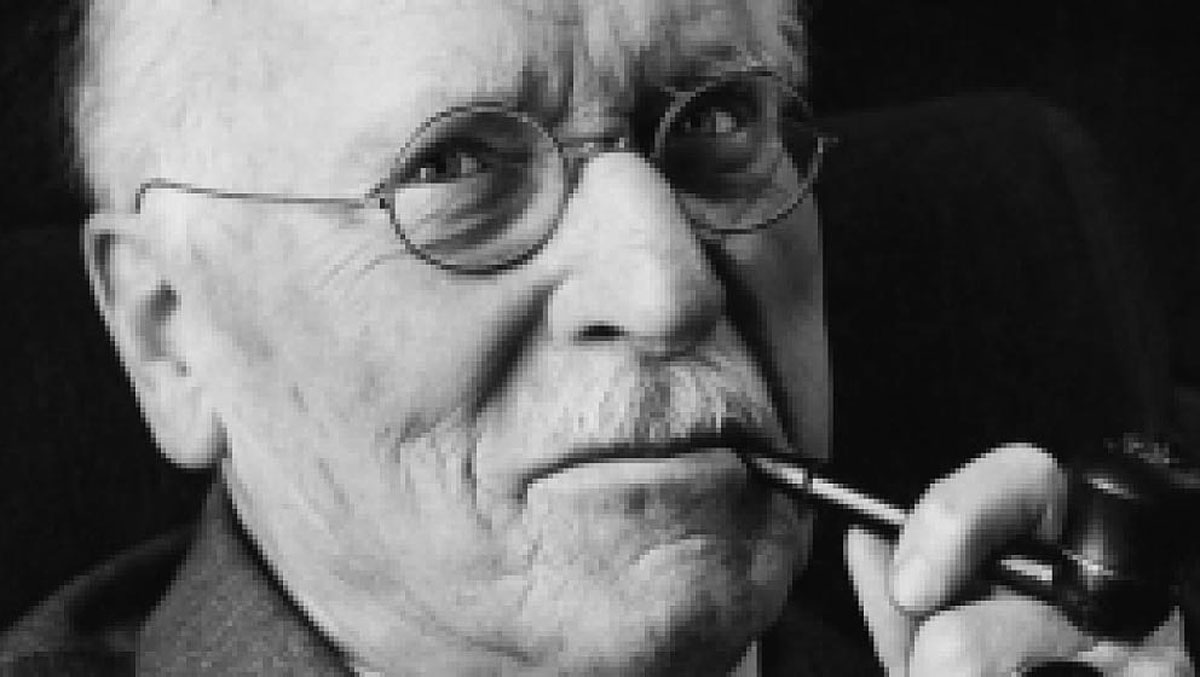

Throughout human history, philosophical and spiritual beliefs also have been called upon to make sense of the unknown. Age-old concepts like fate, destiny, providence, and grace have certainly been used to interpret and frame auspicious events, usually with the idea that nothing in life occurs by accident or coincidence. Religious ideologies, too, have long provided the basis for labeling wondrous events as miracles, acts of divine intervention, or evidence of God’s will and handiwork. But Swiss psychologist, Carl Gustav Jung, had his own theories about these types of events. While not to discount the possibility of a divine agency behind the phenomena, Jung believed that many of life’s coincidences could be attributed, at least in part, to the activities of the human psyche. He also believed that when something occurs in a meaningful way and appears to defy all rational explanation, it moves away from the domain of mere coincidence and into a special category of human experience, which he called synchronicity.

Sunburst over Limousin, France

Jung's Theory

Jung’s concept of synchronicity is presented in a manuscript that he authored in cooperation with renowned physicist Wolfgang Pauli, entitled, “Synchronicity: An Acausal Connect Principle“. The work was first published in the 1952 edition of Jung’s “Collected Works”, which followed the release of an essay entitled, On Synchronicity, appearing in the 1951 edition of his Collected Works. While Synchronicity was a groundbreaking work in terms of its theoretical contribution, Jung was certainly not the first to theorize about life’s coincidences. In fact, before the release of his manuscript, the issue had attracted the attention of such noteworthy individuals as Arthur Schopenhauer (1891), Paul Kammerer (1919), Wilhelm von Scholz (1924), John William Dunne (1938), and even Albert Einstein (1918), whom Jung credits as catalyzing his thinking on the matter. Jung, however, was the first psychologist to formally define synchronicity and connect it to the human psyche.

While Jung initially became intrigued by the concept of synchronicity in his early twenties, he kept his ideas private for some time. In fact, it was not until 1930, during a memorial address for sinologist, Richard Wilhelm, that Jung publicly used the term synchronicity. Jung gradually became more outspoken on the matter, and during his Tavistock Lectures in London in 1935, he referred to synchronicity as “a peculiar principle active in the world so that things happen together somehow and behave as if they were the same, and yet for us they are not.” Over the years, the concept gathered momentum in Jungian circles, and it soon became a regular part of Jung’s lectures. Finally, in 1949, Jung offered his first full description of synchronicity in the foreword to the Wilhelm-Baynes translation of the I Ching or Book of Changes (1950), although his ideas were still not in manuscript form. In retrospect, it appears that Jung was allowing his thoughts on synchronicity to incubate and mature before officially presenting them. When Synchronicity was finally published in 1951, Jung explained in the forward: “In writing this paper I have, so to speak, made good a promise which for many years I lacked the courage to fulfill. The difficulties of the problem and its presentation seemed to me too great; too great the intellectual responsibility without which such a subject cannot be tackled…”.

Initially, the manuscript was met with great criticism by the Psychology community and became regarded as a controversial work. The problem, aside from the fact that it ran contrary to the deterministic and Freudian-based perspectives of the time, was that it drew into the field of psychology a collection of experiences that many considered reminiscent of superstitious thinking. Jung, of course, was well aware of the sentiments of his time. He even warned his readers in the forward to the book to be prepared to “…plunge into regions of human experience which are dark, dubious, and hedged about with prejudice.” But his intent in writing Synchronicity was not to lend credence to age-old superstitions or condone magical ways of thinking. Quite the contrary, Jung hoped his ideas might clear away some of the mystique surrounding this aspect of human experience. He also hoped his perspectives would provide the foundational thought necessary, as Jung states, “…to open up a very obscure field which is philosophically of the greatest importance.”

Jung came to regard the concept of synchronicity as one that not only pertains to the field of psychology, but physics, philosophy, and religion as well. Recognizing the magnitude of the concept and that his ideas barely skimmed the surface, Jung submitted his synchronicity theory as an incomplete work. It was a beginning nonetheless, and one that he hoped would inspire further study. Over the years, countless theorists have drawn upon Jung’s theory as a reference point for exploring and pushing forward this tenuous and rich area of psychology. However, despite all the assertions, criticisms, clarifications, and elaborations that this work has evoked since its first release, Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle by C. G. Jung, still remains the preeminent theoretical framework for understanding synchronicity.

Synchronicity vs Coincidence

Perhaps the best way to start describing synchronicity is to delineate how it differs from coincidence. A coincidence, stated simply, occurs when two or more events have some intriguing aspect in common. While the same could be said of synchronicity, a synchronistic experience differs in that it always involves three key components:

- Inner-outer connection

- Connection through meaning

- Inexplicability

The first element, an inner-outer connection, pertains to Jung’s basic definition of a synchronistic event. Synchronicity involves the process of seeing a connection between an internal event, which is psychological, and an outer event which is observable in the physical world. The internal event may involve anything from general thoughts and ideas, to intuitions, dreams, or an emotional state. The external event may consist of anything that occurs outwardly in life—from conversations or encounters with people, to accidents, discoveries, or experiences with nature. It may even involve something as simple as hearing a single word or seeing a specific object which relates directly to something thought or otherwise experienced psychologically. Synchronicity then involves the observation of a life event that corresponds directly with something in one’s psyche. Stated another way, when something in one’s mind “clicks” with something in the world, this is indicative of synchronicity.

Near Covent Garden, London

By contrast, a coincidence does not require this kind of inner-outer connection. Although a coincidence may involve a psychological component, more often it involves the act of observing an unusual correspondence between two or more external things. For example, a couple on a first date may suddenly realize that they were born on the same day, or two college students comparing schedules for the coming semester may find that they have enrolled in the exact same courses. When interesting parallels like this occur, usually one person will remark, “Wow, that’s weird,” or “What a coincidence!” But this is not the same as experiencing synchronicity, and the difference lies in the fact that these kinds of events do not involve a connection to something psychological.

The second way that synchronicity differs from coincidence is through the presence of meaning. Meaning is essential to synchronicity because it provides the connective link between the internal and external events. Plus, the involvement of an inner, psychological component has the effect of personalizing the experience, which makes it all the more meaningful. Noticing a coincidence, on the other hand, merely involves the act of observing a peculiar correspondence between two or more events, which makes the correspondence more detached from oneself. For example, in the case above with the couple with identical birthdays, the recognition of the correspondence involves the mental act of linking two observable factors together and taking note of their peculiarity. Since there is no internal event, the connection merely becomes an interesting observation. By contrast, consider the experience of thinking about someone right before they call. This differs from coincidence because internal events (thoughts) are personal to us—we own them. Hence, the act of seeing a correlation between one’s private inner world and something in the outer world has the effect of imbuing the whole experience with personal meaning. The issue of “what constitutes meaning” is a key consideration in synchronicity, and it is one that will be addressed in a later chapter. But for now, what is most important is the idea that synchronicity always involves the act of connecting an inner event to an outer one through meaning, and it is through this inner-outer connection that the experience gathers significance and pulls away from coincidence.

The third condition that separates coincidence from synchronicity is inexplicability. According to Jung, for an event to be considered true synchronicity, it must arise in some highly illogical fashion, as if the experience was somehow able to slip by or override the traditional laws of cause and effect. For instance, imagine that a man dreams that he wins the lottery by selecting six numbers, and the next week, he plays his dreamt numbers and he wins. An incident like this would appear to defy all logical explanation—not because of the odds against hitting all six numbers, although this is indeed out of the ordinary—but because he dreamt of the numbers beforehand. By the traditional laws of causality, life unfolds in a linear, sequential fashion (A + B + C = D) with every event being caused by a preceding event or chain of events. So how would it be possible for someone to see or know of something before it happens? This indeed is one of the questions that synchronicity raises. And while there are certainly other ways that an experience can appear inexplicable, aside from the “out-of-order” type depicted here, as a general rule, a synchronistic experience will appear inexplicable when it involves an inner-outer correspondence that, from all angles, has no causal grounds for being there.

Causality is something that becomes so deeply ingrained in one’s thinking that it is rarely given a second thought. When a ball is kicked, it moves. When we strike a match, it ignites. As Newton’s Law explains, with every action or cause, there is a necessary and sufficient reaction which immediately follows. This law is the essence of causality. But causality is not something that is learned through a course in physics—rather, it is an understanding that is acquired instinctively and necessarily through the course of life. As Piaget (1957) explained, the human mind has an inherent need to understand and anticipate the activities of the world, and since the world operates by certain consistent principles of cause and effect, it is through the process of observing the world, which begins at the onset of life, that we humans come to view events as always unfolding in a logical, linear fashion. This “strictly causal” view of the world is strongly reinforced in our minds in childhood through the lessons we receive at school and at home, and through the messages we hear and internalize through our culture. We begin placing our faith in causality very early, and as this knowledge is tested and develops over time, it becomes a basis for understanding reality. This is why an encounter with synchronicity can have such a jarring effect—because it calls into question our basic understanding of how the world works. Invariably, some confusion and grappling will follow a synchronistic experience as one searches for explanations and uses norms to judge the probability of the occurrence. But if the experience is truly inexplicable, it will not be easily reconciled through the mind’s traditional model of linear causality.

A coincidence, on the other hand, does not usually have this kind of unsettling effect, nor does it trigger a search for explanation. In general, to judge an event to be a coincidence involves the act of attributing some logical cause or explanation to the event, despite the fact that the real explanation is unknown. For example, when a person says, “Oh, it’s nothing but a coincidence,” this essentially means that the person has assessed the overlapping events and has come to the conclusion that while there may be an interesting connection or parallel between them, there is no real need to search for a reason behind the occurrence. In essence, the label of coincidence provides the explanation. An experience of synchronicity, on the other hand, is much more difficult to dismiss. This is largely because it involves a psychological component, and it is difficult to lend a rational or causal explanation for why something psychological would coincide with something physical. It simply runs contrary to what we know to be true. So with synchronicity, the traditional laws of cause and effect are generally found to provide an inadequate means for even speculating on a possible explanation. In summary then, the act of labeling an experience as a coincidence is one where a logical explanation is presumed to exist somewhere, whereas an experience of synchronicity leads to the sense that no logical explanation is available anywhere.

There are times, however, when an experience will resemble synchronicity despite the fact that it does not display a clear-cut defiance of causal laws. These kinds of experiences create a gray area for synchronicity because they are based more on improbability than inexplicability. For example, imagine that a woman flies to New York City to surprise an old friend, and upon arriving, she stops at a local market for a newspaper where, ironically, she bumps into her friend. Clearly, the chance of this happening would be extremely low, but the occurrence does not lie outside the realm of possibility in terms of causality. Since there is nothing blatantly out of sequence here (as with the previous lottery example) and since the internal factor is less pronounced, their meeting could just be a fluke occurrence. Nevertheless, the odds of the event occurring are highly unlikely, and it is the recognition of this fact that draws attention to the event in the first place. While causality has to do with “the way things happen in life,” probability has more to do with the way we would expect things to happen, or the way that our minds imagine things should happen. Consequently, with events that appear improbable, instead of wailing a direct assault on one’s causality model, these events will simple appear unusual with respect to the laws of probability. There are, of course, degrees of probability, and the degree to which an experience appears improbable will or may affect the way that the observer assesses the experience. For instance, in the example cited above, if the local market was within a few blocks of the friend’s house, the meeting becomes easier to reconcile. However, if the meeting takes place in a small out-of-the-way market on the outskirts of the city, the improbability is much higher and it is in cases like these that it can be difficult to dismiss the incident as mere coincidence. This is where the issue of inexplicability gets tangled up with probability, and it is also here that the concept of synchronicity opens itself up to debate.

Psychologist Charles Tart once made the comment that events sometimes masquerade as synchronicity in the sense that they appear incomprehensible on the surface, but have causal roots nonetheless. So how are we to know the difference between the improbable and the inexplicable? Well according to Tart, “…absolute synchronicity occurs when no causal mechanism could have been responsible.” Or as Jung once said, “…their ‘inexplicability’ is not due to the fact that the cause is unknown, but to the fact that a cause is not even thinkable in intellectual terms.” But this raises the question of how to regard the term “unthinkable” since what may be unthinkable to one person may not be unthinkable to another. And to be honest, even Jung himself cited examples of synchronicity that are within the realm of probability. Nevertheless, the condition of inexplicability is a necessary one because it elevates the standard of what is to be considered synchronicity, and it implies that before an experience is to be identified as synchronicity, all avenues of logical explanation must be explored thoroughly.

Carl Gustav Jung, c. 1960

[public domain]

The Matter of Time

The term synchronicity is actually a good one because it reflects the irony that typically surrounds these experiences, as well as the idea that the inner-outer events will appear to fit together like synchronized gears on a clock. Synchronicity, however, is not always synchronized. To say that something is synchronized, like synchronized swimmers or synchronized watches, literally means, “happening or existing at the same time” (Oxford American Dictionary, 2021). But with synchronicity, the inner and outer events do not always occur at precisely the same time. Very often in fact, one event will follow the other in time by a minute, an hour, or even by several months or longer. And yet, the events will be connected. For instance, if you have a dream, and the dream becomes eerily reenacted in real life a few days later, the two events will still be linked in spite of the time gap because of the unmistakable correspondence between them. When this occurs, the lack of synchrony in the situation becomes irrelevant because it is their connection through content and meaning that binds them. This type of synchronicity is evident in the case of Rosalind Heywood (Henry, 1993). Heywood reported that once while flying in an airplane, she found herself contemplating a particular poem portraying wasps in a positive light. Then later, as she was exiting the plane, a swarm of wasps gathered above her head and hovered there for some time, as if her previous thoughts had somehow summoned the wasps to her. Ironically too, Heywood was not stung, which only reinforced the correspondence between her previous thoughts about good wasps and her experience exiting the plane.

According to Jung, when synchronicity involves some lag time between the psychological event and the physical event, the experience should be designated as synchronistic rather than synchronous, since it does not occur in a synchronous manner. This is not to say that the timing of events is not critical in some cases. Indeed, synchronous synchronicity does occur, and the case of Judy Vibberts illustrates this well. While relaxing one day at around 4:30 in the afternoon, Vibberts was suddenly struck with excruciating abdominal pains, followed by a splitting headache. Then later that evening, Vibberts discovered a dear friend of hers had been in a serious car accident at around 4:30 in the afternoon, suffering injuries to the abdomen and head (Bolen, 1979). In this case, Vibberts’ experience in the park (which was both physical and psychological) corresponded directly to her friend’s accident, thus creating synchronous synchronicity. Events like these that are woven together and joined by time gather meaning simply through their uncanny overlap.

Summary

Synchronicity has been defined as a rare human experience that differs from coincidence through the presence of an inner-outer connection, meaning, and inexplicability. While these three elements contribute important pieces to the phenomenon, individually, they do not function as independent factors. On the contrary, they are interrelated, and as such, they can gain prominence and intensity through their relationship to one another. For instance, the more precise the correspondence between the inner and outer events, the more meaningful and inexplicable the event will appear. Similarly, the more poignant and precise the meaning in the experience, the more inexplicable the event becomes—or conversely, the more inexplicable the event appears, the more it gathers meaning. It is also important to recognize that while the timing between the inner and outer events can often act as an intensifying agent, as with synchronous synchronicity, in many cases, the timing of events will be relatively unimportant because of the binding quality of meaning.

Finally, because synchronicity is an inexplicable event that defies the laws of causality, it often will evoke a temporary state of confusion in the observer. This state of disequilibrium and the ensuing quest for a logical explanation is largely driven by the instinctual human need to understand, anticipate, and feel secure in the world. The issue of inexplicability, however, is a tenuous one because the act of determining what is inexplicable or unthinkable is relative to the individual. This is particularly true when it comes to experiences that are highly improbable but do not completely defy the laws of causality. Fortunately, Michael Fordham (1957) offers some clarity in this area. He explains that what is most important in synchronicity is that the individual believes that a cause has been undermined and that they feel something special has happened to them. Fordham may be a bit lenient here, but his sentiment is a good one. Because of the peculiar nature of these experiences and because there are degrees to which all three factors may participate in any given experience, it would be impossible to draw a line distinguishing where coincidence ends and synchronicity begins. In reality, there exists some kind of continuum between them with common coincidence on one end and mind-blowing synchronicity, as with a miracle, on the other. And while the condition of inexplicability may help draw a theoretical distinction between coincidence and synchronicity, ultimately it is up to the individual to interpret the nature and significance of their experience based upon what they observe about it on an objective level, and what it means to them on a personal level.